Thomas Jefferson’s Original Graveyard Monument

at the University of Missouri

© By John Hamilton Works Jr 7th generation descendant

The history and current location of the original monument erected over Jefferson’s grave is very interesting.

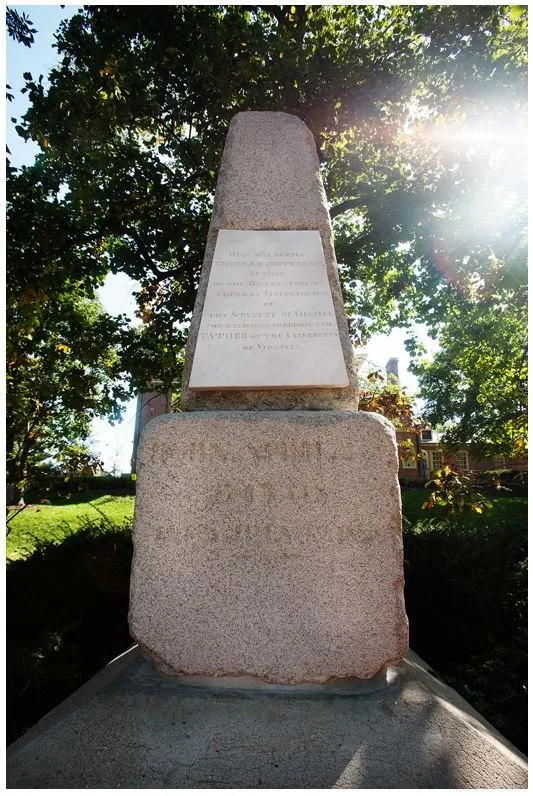

Jefferson’s tombstone was not a simple grave marker. The 3rd President of the United States left very detailed instructions for a 3-part stone sculpture—a granite obelisk that would sit atop a granite cube and be adorned with an inscribed marble plaque. Jefferson also left a sketch and specific instructions for the size and material for the monument, and the inscription he would prefer. "Could the dead" Jefferson had written on the back of a partially mutilated envelope "feel any interest in monuments or remembrances of them", he would prefer "on the grave a plain die or cube 3 feet without any moldings, surmounted by an obelisk of 6 feet height, each a single stone: on the faces of the obelisk the following inscription and not a word more –

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom

and Father of the University of Virginia

On the Die

Born April 2, 1743 O.S.

Died July 4, 1826

By these as testimonials I had lived and desire most to be remembered."

The "O.S." refers to the Old Style or Julian calendar in-use when he was born. (His birthday under the New Style or Gregorian calendar is April 13). Jefferson further directed that these memorials be made from "the coarse stone of which my columns [at Monticello] are made, that no one might be tempted hereafter to destroy it for the value of the materials."

Jefferson left these instructions for his tombstone

Jefferson himself wrote what he wanted written on the stone. Scholars find it interesting that he left out many of his other accomplishments, including (i) being the 3rd President of the United States (for 2 terms) during which he dispatched Lewis & Clark on the expedition to the Western Territory, (ii) having been the principal negotiator of the Louisiana Purchase (which nearly doubled the size of our young nation), (iii) serving as the Governor of Virginia, Ambassador to France, Secretary of State, and Vice President, (iv) having proposed using the decimal system for the U.S. currency, (vi) having proposed building an interstate highway system, (vii) founding the U.S. military academy at West Point, (viii) donating his personal library to the U.S. Government which became the nucleus of the Library of Congress, and (viii) his achievements in architecture, which involved helping design Washington, D.C., the Richmond state capitol, and Monticello, plus (ix) his love of antiques, music, gardening, scientific instruments and collections of natural history.

The obelisk was fabricated by John M. Perry and James Dinsmore, who earlier helped build Monticello as carpenters. The actual monument followed Jefferson’s instructions to the letter, with one notable exception. Because of the coarseness of the specified granite, it was not possible to cut the inscriptions into the face of the obelisk—so a 160-pound marble plaque was engraved instead.

At the time of his death, Jefferson's estate was in debt, and except for possibly some smaller and more temporary markers, it appears that no permanent obelisk was erected until 1833, some 7 years after his death. Visitors flocked to Monticello to see it after it was erected in 1833, but souvenir hunters took to chipping off small chunks of the granite base. The marble plaque remained intact but soon loosened from the granite following the ”rude treatment the monument received”, wrote one observer at the time. Horrified that the whole monument would soon be ruined, Jefferson’s heirs ordered a replica be placed in the graveyard with the original stored inside Monticello. (Note that today grave desecration is illegal in many states, including Virginia where Jefferson’s replacement grave marker is located. See VA Code Ann. Section 18.2-127 (making grave desecration a Class 6 felony)).

The monument, shown here in its original location in the graveyard at Monticello, before it was given to the University of Missouri in 1883

A government campaign was then begun to replace the monument with a larger copy. On May 3, 1878, Congress passed a joint resolution providing for the erection of a new monument over Jefferson’s grave and appropriated $5,000 for it. However, it was premised upon the condition that the owners of the graveyard would transfer to the United States an area of 2 square rods (33' x 33') including Jefferson's grave, and give the public free right of access to it. When transfer of title was being arranged, Jefferson's descendants naturally felt reluctant to deed away his grave, even to the U.S. government. Some of them, who had close relatives buried in the lot demanded by the government, felt that deeding their graves away would be an almost greater sacrifice than they could bear. Still, feeling and sentiment might have been met, but other obstacles arose in the way of granting the conveyance. For example, many of the descendants were minors, and before the parcel could be conveyed the matter would have to go through the courts, which would involve great delay. Further, the conveyance could not be given by the owners of the graveyard without obtaining the consent of the Virginia legislature, which also would involve yet more delay.

Congress did not act for 4 more years, when another joint resolution of Congress was approved on April 18, 1882, appropriating $10,000 for the erection of a new monument. This time it prescribed no conditions, but simply directed the appropriation of funds and their expenditure under the direction of the U.S. Secretary of State.

On April 18, 1883, the new obelisk was moved to Monticello. It weighed about 16,000 pounds, and 10 horses were required to move it from Washington to the new location. And the new obelisk was twice the size of Jefferson's original design.

When the new monument was built, Jefferson's grandchildren received many requests for the old one. One such request came from the University of Missouri. Missouri was important to Jefferson because it was within the vast region of the Louisiana Purchase, which Jefferson orchestrated in 1803 while President, which doubled the size of the United States. This request was strengthened because of Jefferson's lifelong labors in behalf of state-supported education—the university was the first public university west of the Mississippi, and in 1862, the university became a public land-grant institution as part of the Morrill Act. The University of Missouri also had projected a curriculum and concept of higher education similar to those Jefferson had put into practice some years earlier at the University of Virginia. In addition, many first- and second-generation residents of Columbia and Boone County, Missouri were originally from Virginia and could claim "cousinship" of one kind or another with Jefferson. The fact that the state capital of Missouri, Jefferson City, was named after Jefferson probably further strengthened the appeal of the University of Missouri's request.

The old monument initially was placed to the right of the entrance to the main building on the University of Missouri campus where it was unveiled on July 4, 1885, the final day of commencement exercises, in a ceremony said to have been the most elaborate in the history of the University. Speeches were made by Thomas F. Bayard, U.S. Secretary of State, George E. Vet, U.S. Senator from Missouri, and Captain James B. Eads, a noted Missouri engineer. The Board of Curators of the University of Missouri adopted a formal resolution of thanks to the donors of the monument and sent them a copy of their resolution printed on a silken scroll, which is now in The Monticello Association’s archives.

The Columbia Missouri Herald of July 12, 1883, commented: "Welcome then any reminder of Jefferson to Missouri. May these souvenirs be a fresh inspiration to Missourians, not only in maintenance of the true principles which underlie the government which he helped to found, but also of the cause of higher education of which he was of all Americans the most conspicuous pioneer." The marker reads as follows: “Placed at the grave of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello, Virginia, in 1826, constructed from his own design, was presented July 4, 1885, by the Jefferson heirs to the University of Missouri, first state university to be founded in the Louisiana Territory purchased from France during President Jefferson’s administration. The obelisk, dedicated on this campus at commencement, June 4, 1885, commemorates Thomas Jefferson, third President of the United States, whose faith in the future of western America and whose confidence in the people has shaped our national ideals, commemorates the author of the Declaration of Independence and of the Virginia Stature for Religious Freedom, founder of the University of Virginia, and fosterer of public education in the United States.”

But thereafter the obelisk and plaque were moved frequently on campus. Although the obelisk sat outside Academic Hall, the tombstone plaque was put inside the building for safekeeping. It stayed there until January 9, 1892 when a fire consumed the entire building, eventually leaving only its iconic columns. Students ran inside to save the plaque, but not soon enough to save it from extensive smoke and heat damage. It was burned, cracked, and broken into 3 pieces, with portions crumbling at the edges. Its left side was slightly higher than its right, and its marble face was sugaring and blistering.

The monument outside Academic Hall after the 1892 fire consumed the entire building, leaving only its iconic columns

The University initially restored it and mounted in a plaster compound. No official report documented how it was reassembled or what materials were used. The plaque was then placed inside 2 wooden boxes, and again put away in an attic. It was stored until completion of a new building in 1895, which in 1922 was named Jesse Hall. For decades the slab was displayed in the cashier’s office’s vault. At some point later it was moved to a corner in the unheated attic and made public appearances on Jefferson’s birthday and the University’s Tap Days.

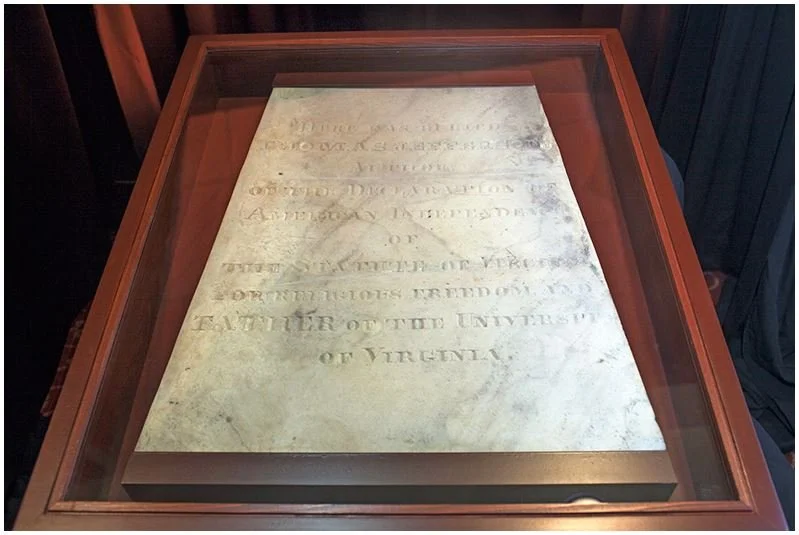

The original plaque in the attic of Jesse Hall at the University of Missouri

For the next 100 years the marble plaque remained stored in a wooden box in a dark corner of the unfinished attic, too fragile to be put on display. In 2005, a group of university administrators decided to do something about it, and finally in 2009, the university decided to restore the marble slab. The University estimated that it probably would take a year to restore it at a cost of more than $250,000. So they approached the Smithsonian Museum, who agreed to take on the restoration project free of charge. (It is rather rare that they take on anything from the outside). The university paid for the initial stabilization treatment and for shipping, and the Smithsonian paid for the entire cost of restoration.

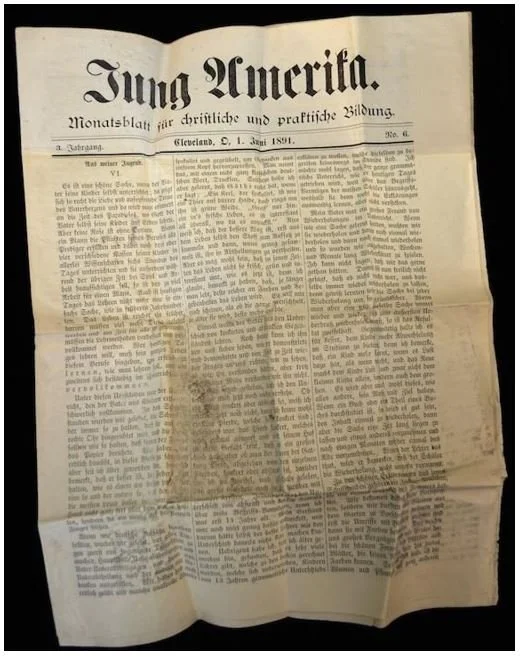

When the plaque was being prepared for shipment, beneath it was a June 1891 Cleveland newspaper, Jung Amerika, written in German. Surrounding the slab was paper stuffing, including one crumpled wad that was a university catalog from 1888 listing university events that coming semester, and a page stated that campus schools and colleges would open on September 10, 1888. These dates are consistent with the plaque being stored in its wooden frame following its rescue from the 1892 fire.

The June 1891 Cleveland newspaper, Jung Amerika, found under the plaque before shipping to the Smithsonian for restoration

Long ago it was speculated that the marble for the plaque probably came from either Vermont or perhaps from the famous marble quarries in Carrara, Italy. Using a stable isotope analysis, the Smithsonian discovered the mystery of the marble’s origin, and determined that the source of the marble was from a quarry in Vermont.

The plaque itself is now on display indoors in the first-floor lobby of the University’s Jesse Hall.

The restored plaque in the lobby of Jesse Hall at the University of Missouri

The plaque was returned to the university in August 2014, and with the help of the Smithsonian Institution, the stone’s original marble epitaph was unveiled with a more durable facsimile on Francis Quadrangle during the university’s week long 175th anniversary celebration from September 15-21, 2014. The university also asked the Smithsonian to make 2 replicas of the tombstone. One of the replicas is used for teaching and the other is adhered to the original granite obelisk and prominently displayed in the main campus quad.

The obelisk itself is contained in an area now called “The Jefferson Memorial Garden” in the university’s Francis Quadrangle, where students and visitors have the opportunity to sit among many of the flowers once found in Thomas Jefferson’s own garden at Monticello, which includes the cardinal flower, columbine, Virginia bluebells, sweet shrub, and Rose of Sharon. The Quadrangle was named to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. A bronze sculpture of Thomas Jefferson, as well as the original obelisk, are also located in the garden. The sculpture of Jefferson, created by Colorado artist or George Lundeen, was unveiled on May 4, 2001. The garden and sculpture were made possible through donations from past and current Trustees of The Jefferson Club, a group of University of Missouri supporters dedicated to quality education.

Bronze sculpture of Thomas Jefferson by Colorado artist George Lundeen

Workmen rotating the granite obelisk 180 degrees so the plaque faces toward Francis Quadrangle

The original granite base and obelisk as finally complete with a

Smithsonian-made reproduction of the marble plaque on view on the campus of the University of Missouri

The monument (before restoration) in the Jefferson Memorial Garden in the University’s Francis Quadrangle

The University of Missouri’s Francis Quadrangle

Sources:

George Green Shackelford's Collected Papers to Commemorate Fifty Years of the Monticello Association of the Descendants of Thomas Jefferson, Princeton University Press, 1965, pg. 9-18, particularly History of the Graveyard at Monticello, by Robert H. Kean

William Peden's booklet The Jefferson Monument at the University of Missouri, which contains Jefferson's original design, and historic pictures of the sculpture at Monticello and Academic Hall

Telephone interview with Ms. Linda L’Hote, Senior Associate Vice Chancellor for Development at the University of Missouri, January 21, 2010

University of Missouri News Release, December 4, 2012

Smithsonian Insider, December 6, 2012

Mizzou Weekly, February 14, 2013, Volume 34, No. 19

Smithsonian Magazine, February 15, 2013

Columbian Missourian, September 16, 2014

Mizzou (the Magazine of the University of Missouri Alumni Association)—November 11, 2014

Funeral Law Blog, December 4, 2014

Smithsonian Magazine, July 2, 2015

Picture of John Hamilton Works, Jr. at the University of Missouri’s Francis Quadrangle taken by a student on Sunday, November 29, 2009 when the author visited the university campus (his mother lived 2 hours away in Kansas City, and after spending Thanksgiving there, he took a day’s side trip to Columbia, Missouri, where the University of Missouri is located). Some of the other pictures in this article are ones he took himself.

© John Hamilton Works Jr

johnhworks@gmail.com